22 May 2025

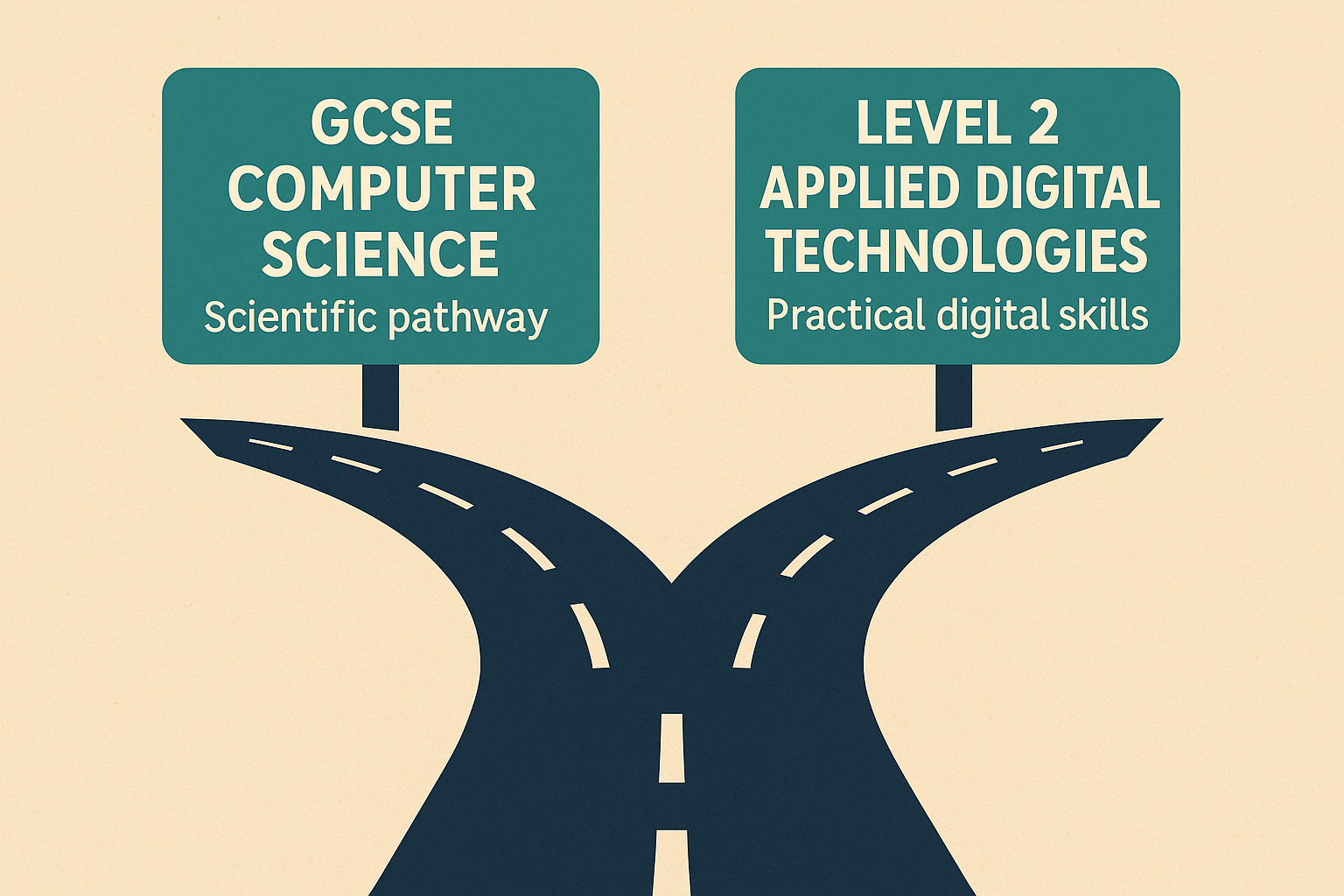

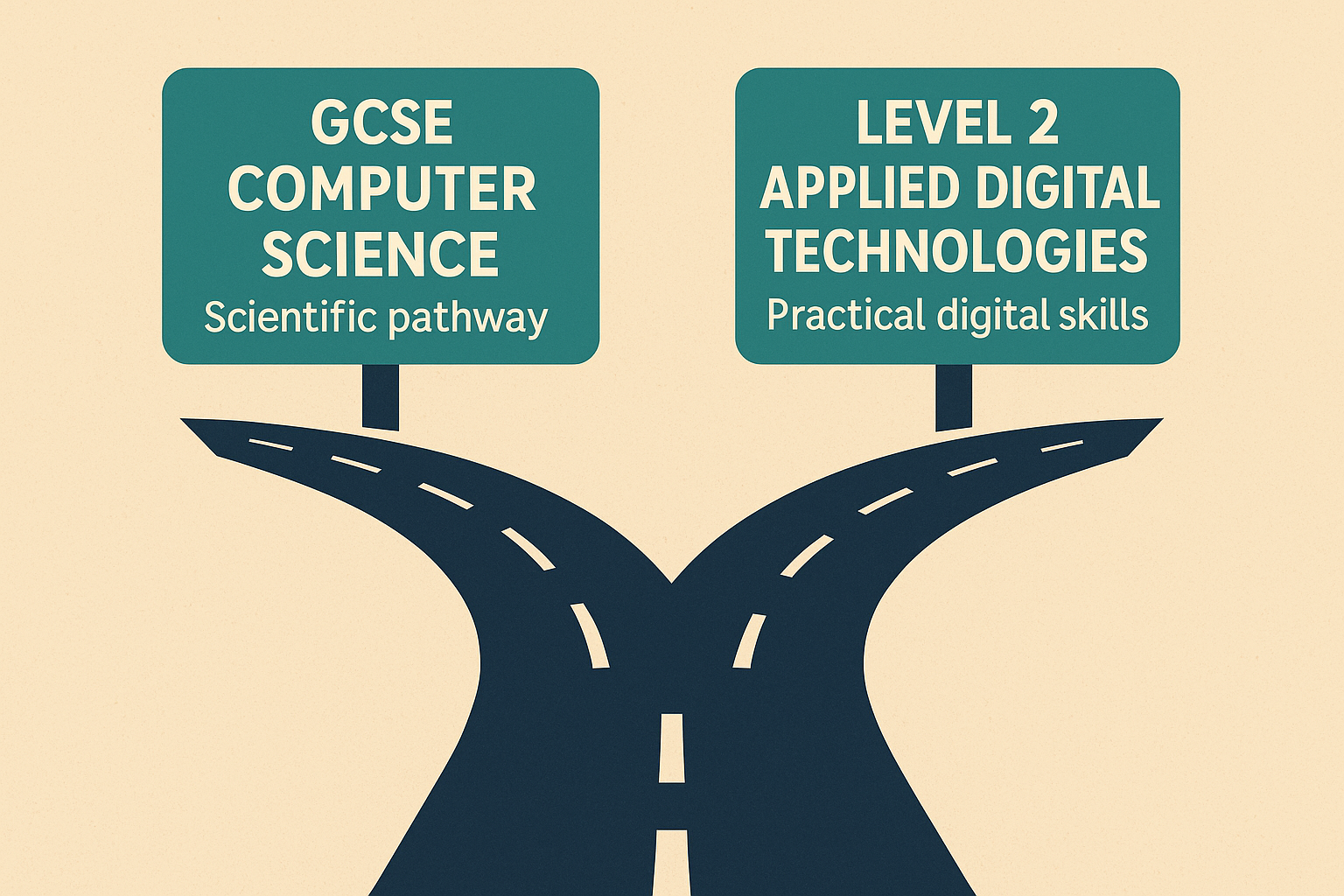

Two Paths Forward: A Dual-Qualification Model for Modern Computing

1. Introduction

The March 2025 Curriculum Review interim report warns that without change, key stage 4 qualifications risk becoming outdated and exclusive. In response to these emerging recommendations, the British Computer Society’s Computing At School Innovation Panel convened on 7 May 2025 to get on the front foot ahead of the final review, presenting three options — including the Berry/Kemp holistic model — to broaden and modernise GCSE Computer Science. Shortly thereafter, Greg King published a thoughtful response, welcoming the debate around digital skills but emphasising the importance of preserving Computer Science as a distinct scientific discipline rather than subsuming it into a broader vocational award.

Building on these discussions, this article argues for a dual-qualification model; GCSE Computer Science must be retained as a robust scientific pathway to advanced study and careers in computing, while a separate Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies qualification — practically assessed to equip a wider demographic with the digital literacies employers demand — should be introduced to sit alongside it.

2. Government Curriculum Review Interim Findings

2.1 Summary of Interim Findings

The March 2025 interim report finds that, despite a “knowledge-rich” national curriculum driving strong attainment in core subjects, the system is “not working well for all” learners — persistent disadvantage gaps remain for socio-economically disadvantaged students and those with SEND. Stakeholders raised concerns that, at key stage 4, an over-packed syllabus and accountability measures such as the EBacc may squeeze out vocational, arts and applied subjects, reducing both curriculum depth and the time available for pupils to engage with non-academic areas.

Crucially, the Review emphasises the need for the curriculum to “respond to social and technological change,” calling for a renewed focus on digital and media literacy, data and AI concepts, and other applied skills to prepare young people for life and work in a rapidly evolving world. Polling of key stage 4 learners and their parents confirms this appetite: over a quarter (27 percent) would have liked more time on digital skills or computing between Years 7 and 11.

2.2 Implications for Computing

While GCSE Computer Science is designed to blend theory and practice, students’ experiences vary markedly by awarding body. Edexcel, for instance, incorporates an on-screen practical paper in which learners complete coding tasks under timed conditions, whereas other boards often assess practical skills entirely through written exam questions rather than any hands-on activity.

The Curriculum Review interim report highlights that reforms at KS4 have shifted the emphasis towards terminal exams — with non-exam assessment reduced or removed in many subjects — so that grades now hinge on “on-the-day” performance. This tightening of exam-only assessment has squeezed out opportunities for students to develop and showcase practical skills over time. Consequently, although specifications nominally aim for a balance of practical and theoretical work, many learners report that GCSE Computer Science can feel overly recall-focused, with too little authentic, project-based experience.

This inconsistency — in which some specifications offer time-limited practical coding tests and others rely solely on written questions — underscores the case for a separate, practically assessed Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies qualification. A new Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies course would guarantee sustained, hands-on development of digital tool-use and real-world problem-solving skills employers demand, while allowing GCSE Computer Science to remain a clear scientific pathway.

3. BCS Online Meeting & Berry/Kemp Proposal

3.1 The “Single Holistic GCSE in Computing” Proposal

At the 7 May 2025 Computing At School Innovation Panel, Prof Miles Berry and Dr Pete Kemp argued that the existing GCSE Computer Science suffers from being “the subject of Computing, but the qualification of CS,” resulting in a qualification that is too narrow, overly theoretical and has driven down uptake — especially after the removal of GCSE ICT, which led to fewer students studying computing, with the greatest declines among girls and disadvantaged learners.

Berry & Kemp marshal compelling data to show why a holistic Computing GCSE is needed. Their proposal is for a single, holistic GCSE in Computing built around three pillars:

- Foundations – core computer-science principles (abstraction, algorithms, data, programming)

- Applications – hands-on use of digital systems and tools in authentic contexts

- Implications – critical digital literacy, societal, ethical and professional considerations

Designed “to address the full breadth of the subject,” it would focus on how individuals, organisations and society use digital technology (not just its internal workings), keep pathways open for later specialisation, play to existing teacher expertise, and promote practical work in assessment.

3.2 Data & Evidence Supporting Their Findings

- Uptake & Equity: Berry & Kemp presented longitudinal entry data showing a sustained fall in Computing GCSE entries post-ICT removal, with a sharper decline in state schools and among girls and disadvantaged pupils — evidence that the current qualification is failing to engage a broad demographic.

- Learner Engagement: Slides entitled “Students Who Found the Topic Interesting (%)” versus “Students Who Found the Topic Difficult (%)” underscored that many learners view the present GCSE as “narrow, dull and hard,” undermining motivation and widening participation gaps.

- Active Learning Benefits: Drawing on Resnick and the Royal Society (2017), they highlighted research demonstrating that project-based, active computing instruction boosts attainment and fosters a more inclusive classroom that attracts under-represented groups in computing.

- Cultural Relevance: Referencing Leonard et al (2021), they warned that a lack of cultural responsiveness in computing content contributes to under-representation of minority ethnic groups. Their three-pillar model explicitly incorporates real-world contexts and critical reflection to broaden appeal and relevance.

By combining robust entry-uptake statistics, learner-survey insights, and a pedagogical framework grounded in active, culturally responsive learning, the Berry/Kemp proposal marshals compelling data to justify a unified, practically assessed GCSE that balances theory with real-world applications and implications.

4. Greg King’s Response

In contrast to Berry & Kemp’s unified GCSE vision, King champions targeted vocational improvements over a wholesale GCSE overhaul. His response lays out four core critiques of the current GCSE Computer Science and offers tightly linked remedies for each.

- Too much recall, not enough problem-solving

- Critique: “The current GCSE … does not prepare students well for A-Level Computer Science because there is too much recall and not enough practical problem solving.”

- Proposal: Introduce a practical endorsement (akin to A-Level sciences) where students build a software portfolio through iterative projects — ensuring real problem-solving experience without affecting the GCSE grade itself. Multiple attempts at each competency reinforce learning over time.

- Vocational courses already cover practical projects

- Critique: “Why make GCSE Computer Science involve creative practical projects when Creative iMedia and Cambridge Technical IT are right there already?”

- Proposal: Before reshaping the GCSE, “fix the issues with the Cambridge Nationals” — refine existing Level 2 vocational qualifications to better serve practical learning, rather than subsuming them into the academic GCSE pathway.

- Lack of collaborative assessment

- Critique: “It in no way prepares students for the collaborative nature of working as a programmer.”

- Proposal: Embed collaborative group projects within the practical endorsement framework, with each student individually assessed (drawing on the model used in GCSE Music), so teamwork skills are built and measured authentically.

- Pitfalls of centre-assessed work

- Critique: Centre-assessed portfolios suffer from vague mark schemes, grade inflation, heavy teacher workload and inconsistent standardisation — “a lottery of management styles and student/parent demographics.”

- Proposal: The practical endorsement decouples hands-on competency from the headline GCSE grade, uses clear, numeric assessment criteria, and allows retakes to ensure fairness — thereby protecting professional judgement and reducing league-table pressure.

King maintains the integrity of GCSE Computer Science as an academic discipline while ensuring practical, collaborative and fair assessment. His approach preserves the existing vocational pathway — calling for its improvement in isolation — and safeguards the scientific rigor of the GCSE by relegating hands-on work to an optional, endorsement-style overlay rather than integrating it into the core qualification.

5. Personal View from an Independent School Subject Leader

Reflecting on both the Berry/Kemp and King proposals and drawing on my own experience leading Computer Science in a high-performing independent school, I present a personal viewpoint below. Although not backed by the same research data of Kemp, I hope it goes some way to reflect the position of other grammar and independent schools that, like me, have spent a decade developing a team and delivering the Computer Science curriculum with the support of senior leadership.

5.1 Popularity of “Computer Science”

In our centre, GCSE Computer Science has grown to become the single most popular option at Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4; 75 percent of Year 9 students selected it (45 percent female) and 63 percent of Year 10 have chosen it (47 percent female). These figures far exceed national uptake rates — both overall and among girls — demonstrating that retaining the title “Computer Science” preserves a clear, rigorous identity that students and parents trust as the gateway not only to A-Level and university study in Computer Science, but also digital scientific life skills.

5.2 Response to Berry & Kemp: Preserve the “Science” in Computer Science

Berry & Kemp note that “Computing is the subject, CS is the qualification,” and advocate a single “Computing” GCSE. From my perspective, however, keeping the name “Computer Science” is vital: it signals the discipline’s scientific foundations and differentiates it from more applied digital courses. Conflating everything into “Computing” risks blurring this distinction and undermining the clear academic pathway.

5.3 Response to King: Practical Endorsement’s Merits and Limits

Greg King’s proposal for a practical endorsement — an optional portfolio overlay, modelled on A-Level sciences — has real strengths. In our delivery of the Edexcel 1CP2 specification, students gain authentic practical coding skills: they write, test and debug programs in a dedicated on-screen exam under timed conditions. However, many other boards still use paper-based practical questions, which cannot replicate hands-on coding. For those specifications, a practical endorsement could guarantee sustained skill development, multiple attempts at each competency, and standardised assessment — while preserving equity of access and the scientific rigour of GCSE Computer Science.

5.4 Transition to Dual Model

While a practical endorsement could shore up hands-on coding in some GCSE specs, it does not address the full breadth of data, media and tool-use skills employers now demand. In the next section, I outline how a dual-qualification model — preserving GCSE CS and adding a Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies award — delivers both depth and breadth.

6. Argument for a Dual-Qualification Model

Combining a preserved GCSE Computer Science with a new Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies course offers the best of both worlds: a clear academic pathway for future technologists, alongside a robust, practically assessed vocational route that meets employer needs and learner interests.

6.1 Retain GCSE Computer Science as a Scientific Pathway

- Academic gateway. GCSE Computer Science delivers the core principles of computation — abstraction, algorithms, programming and data representation — forming the essential foundation for A-Level study and degrees in computing. As a distinct “Computer Science” qualification it signals a rigorous, discipline-specific route that students and parents recognise and trust.

- Demonstrated demand. National polling shows that 22 percent of KS4 learners and 27 percent of their parents wished they had spent more time on “digital skills or computing” between Years 7 and 11 — evidence that the appetite for computing remains strong and growing.

- Employer confidence in academic routes. The Review finds that A-Level pathways remain “strong, well-respected and widely recognised,” with 82 percent of A-Level students progressing to higher education by age 19 — underscoring the value of preserving a pure academic Computer Science track.

6.2 Introduce a Separate Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies Qualification

A standalone Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies award would fill the practical-skills gap that neither a GCSE endorsement nor on-screen exam can fully cover. Built squarely around Berry & Kemp’s Applications pillar, this qualification would:

- Deliver core digital competencies through sustained, project-based units in:

- Data skills – collection, cleaning, analysis and visualisation

- Digital media production – graphics, audio/video and interactive content

- Tool fluency – productivity suites, collaboration platforms and basic automation scripting

- Guarantee authentic assessment by making NEA the bedrock of the course (for example, a 70 percent coursework / 30 percent short exam split), so students learn iteratively—free from “on-the-day” pressures.

- Address employer needs directly: industry surveys show over half of entrants lack practical data, media or collaborative-tool expertise; this award would certify those exact capabilities.

- Maintain vocational clarity by naming it “Applied Digital Technologies,” ensuring it stands apart from the theoretical CS syllabus and avoids the confusion of a merged “Computing” GCSE.

- Ensure equitable access by offering mixed-mode delivery (digital NEA and paper-based alternatives) so schools without extensive IT infrastructure can still participate fully.

This design secures a clear vocational route — one that complements and never dilutes GCSE Computer Science — while equipping every learner with the hands-on digital literacies employers demand.

6.3 Benefits of the Dual Model

- Equity of access. Schools without reliable on-screen exam infrastructure can still deliver the Applied Digital Technologies course via paper-based or mixed-mode NEA, ensuring no pupil is disadvantaged by hardware constraints.

- Clarity for learners and employers. Distinct qualifications map directly to progression goals — academic students advance to A-Levels, while vocational students acquire industry-relevant tool skills with clear certification.

- Flexibility for all learners. The two-route system caters to high-achievers aiming for computer-science degrees, as well as the wider cohort seeking practical digital competence, without one qualification diluting the other.

In summary, preserving GCSE Computer Science alongside a purpose-built Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies qualification delivers both depth and breadth, securing rigorous academic progression and equipping every student with the real-world digital literacies employers demand.

7. Conclusion

The evidence from the Government’s interim report, the BCS Innovation Panel’s Berry/Kemp proposal, and Greg King’s response converges on one clear imperative: maintain GCSE Computer Science as a distinct scientific pathway and introduce a complementary Level 2 Applied Digital Technologies qualification to deliver the hands-on data, media and tool-use skills that employers and learners alike demand. This dual-qualification model secures both academic depth for future technologists and practical breadth for the wider cohort.

Discussion

Please login to post a comment