27 August 2025

#BackToTheFuture

Wow! I have had an amazing day visiting for the very first time the Museum of Computing History in Cambridge. I am dumbfounded to think that it has been all this time since its establishment in 2013 at its current (August 2025) industrial warehouse location that I’ve made the effort to visit. And this is several months after being in e-mail correspondence with the Museum’s Head of Learning Dr Anjali Das. Anyway, hoping this blog will make up for all of that lost time and mark the start of a more active collaboration given the relative ease travelling to the Museum from my corner of North London.

Although the collection is obviously nowhere near the scale of the galleries and displays which tourists from around the globe travel to see in London, the Museum of Computing History has in my mind created a wonderful timeline of both technological history as well as a beautiful chronology of video gaming. Not overfilled with small inscriptive detail, the Museum seems to have adopted a much more interactive approach where visitors can handle the artefacts on display and experience what it must have been like to either play or use the equipment when they were originally in use.

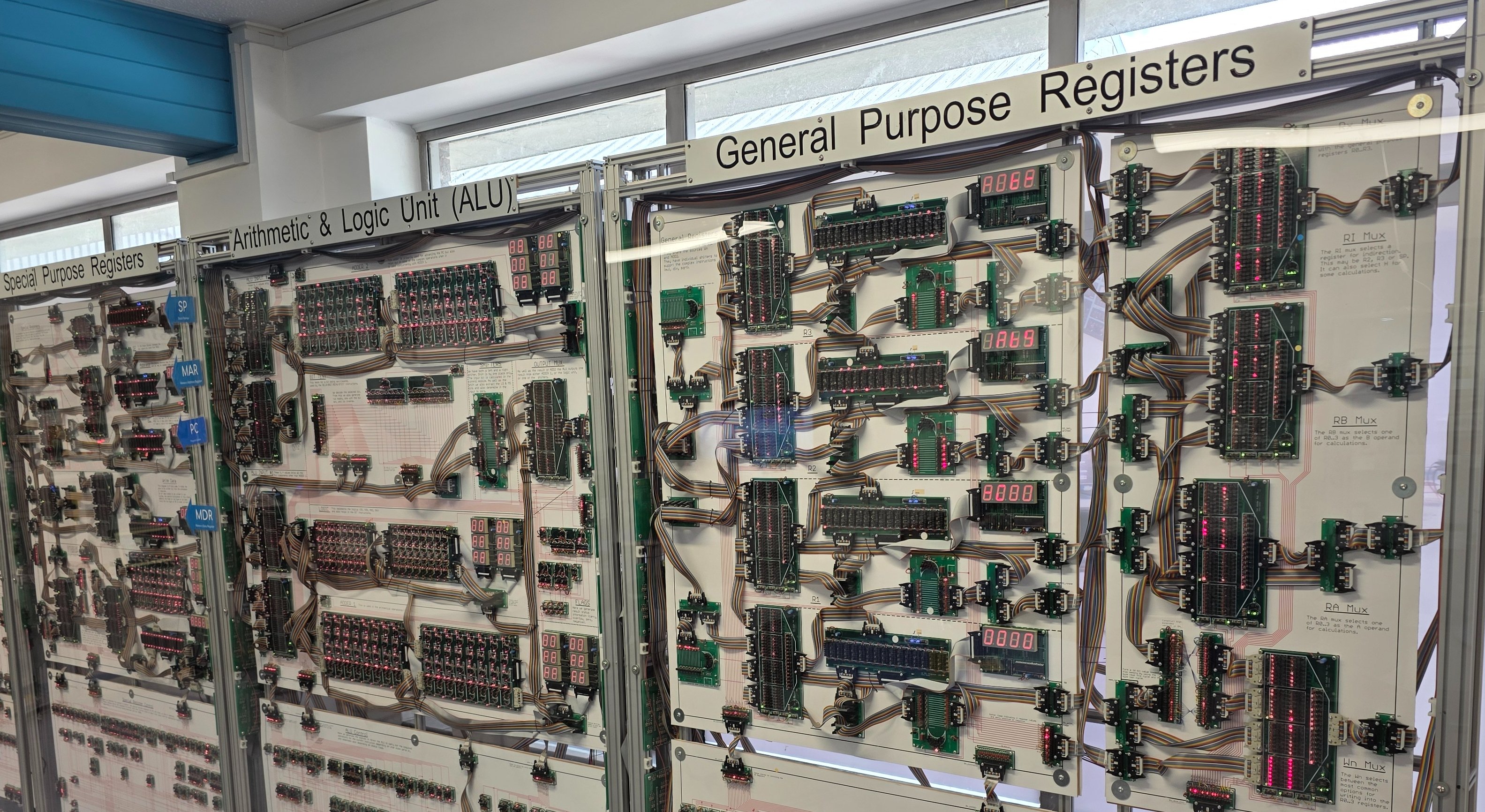

Having had a very active interest in technology since 1982 and a little before that when I began Secondary school, the collection at Cambridge seemed to begin with the machines of the late 1930s with their supersized valves and transistors encased in Bakelite and metal rectangles the width of range cookers and height of fridge freezers. Their industrial appearance were a reminder of how off-putting and seemingly inaccessible computer engineering seemed to be to anybody other than those in commerce (tracking and transmitting stock market prices), academia (such as that by Nuclear Scientists at Liverpool University according to Bletchley Park) and the military.

It was not until the 1950s that keyboards were incorporated into these super-sized processors – essentially the emergence of electronic typewriters which had the capacity for data processing, storage and telex- based communications. Electronic typewriters themselves can be traced back to the 1920s and created to speed up the typing process with their automated carriage return and automated key motion. That last sentence might have been incomprehensible to some but to those like me who learnt to use a QWERTY keyboard using a manual typewriter as I’m sat here typing this blog on my now vintage and discontinued Pixelbook Go from 2020, the ease, speed and efficiency with which the words are aligned and scroll down the screen are very different to the clunky hammering action of manual typewriters. This would also explain why compared to my typewriting speed on a manual typewriter in 1986 of 29 words per minute, children as young as aged 7 can achieve much faster typing speeds when they become keyboard proficient.

It was wonderful to see the timeline of computing in schools with the Commodore PET from 1980. Astonishing to think that learning programming in 1980 according to the Museum’s incredible curation and collection team was the reserve and province of Universities. Reminds me how I was only introduced to ‘code’ and create web pages using html at University in 1997 where web page design is currently (August 2025) taught to children as young as aged 8.

I was so excited to see working models of my very first home computers – the Commodore Vic 20 from 1982 and the BBC Micro from 1984 displayed in arrangements of my teenage dreams. Also on display is an Apple IIe from 1983 which a family friend had, evoking memories of envy as we would spend time together learning how to program in the version of BASIC which I learnt from a display at the Museum was developed by Bill Gates.

The Lottery funded Office exhibit of the 1980s took me back to when I began working with the IBM PC AT, push button Statesman telephone from British Telecom with acoustic coupler modem. By the end of the 1980s and the early 1990s, the ubiquity of IBM clones running Windows 3.1 released in 1992 was evident in the Museum’s collection of working models as the display seems to skip from the Amstrad PC1512 in 1986 to the range of PCs from Compaq running Windows 95. Personally, over that time, I had a succession of IBM clone towers at home which cost somewhere in the region of several hundred pounds including the very physically hefty CRT based colour monitors.

The collection of course being Cambridge based would not be complete without celebrating local legend Sir Clive Sinclair and the range of products from calculators to the ZX Spectrum from the 1980s. The calculators were a reminder of how I tried during my time at Secondary school to practice building my own calculator that was able to perform more complex calculations beyond the essential arithmetic operations. That interest was very short lived since electronic components were beyond my pocket money budget and my parents (quite rightly looking back) discouraged me from soldering given the safety risks at the time. Perhaps if I pursued my curiosity into electronics as Eben Upton of Raspberry Pi did, my story since 1985 when Marty McFly and Dr Emmett Brown began their flux capacitor time travelling adventures, my 2015 might not have been starting as a classroom teacher at the amazing school I am still working for. The power of love is a curious thing...

Discussion

Please login to post a comment